Taming the Crypto Wild West: How the Sherman Act Shapes Stablecoins and Blockchain

Applying the Sherman Antitrust Act to Stablecoins and Blockchain: An Emerging Legal Frontier

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 stands as a cornerstone of U.S. competition law, designed to curb monopolistic practices and promote fair market competition. Its two primary provisions—Section 1, which prohibits agreements that unreasonably restrain trade, and Section 2, which addresses monopolization or attempts to monopolize—have historically targeted industries ranging from railroads to big tech. As stablecoins and blockchain technology reshape the financial landscape, questions arise about how this century-old statute applies to these decentralized, digital innovations. This article explores the potential application of the Sherman Act to stablecoins and blockchain, examining key legal concepts, market dynamics, and regulatory challenges without relying on comparative charts.

Stablecoins and Blockchain: A New Economic Paradigm

Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies pegged to assets like the U.S. dollar to maintain price stability, facilitating payments, cross-border transactions, and decentralized finance (DeFi). Blockchain, the underlying technology, is a distributed ledger that ensures transparency and immutability, enabling trustless systems without traditional intermediaries like banks.

As of early 2025, the global stablecoin market exceeds $230 billion, with major players like Tether (USDT) and Circle (USDC) dominating issuance. These technologies challenge conventional financial systems by offering faster, cheaper transactions and financial inclusion for the unbanked, but they also raise concerns about market concentration and anti-competitive behavior.

The decentralized nature of blockchain complicates the application of antitrust law. Unlike traditional industries with clear corporate hierarchies, blockchain networks often involve diffuse participants—miners, validators, developers, and users—operating across jurisdictions. Stablecoin issuers, however, resemble traditional financial institutions in their control over token supply, reserves, and governance. This duality—decentralized infrastructure paired with centralized issuance—creates a unique antitrust landscape.

Sherman Act Section 1: Restraints of Trade in Stablecoin Ecosystems

Section 1 of the Sherman Act prohibits contracts, combinations, or conspiracies that unreasonably restrain trade. In the stablecoin context, potential violations could arise from collusive agreements among issuers, blockchain platforms, or related entities. For instance, if dominant stablecoin issuers like Tether and Circle coordinated to exclude smaller competitors from major blockchain networks (e.g., Ethereum or Solana), this could constitute an illegal agreement. Such collusion might involve restricting access to liquidity pools, manipulating transaction fees, or pressuring exchanges to delist rival tokens.

Another scenario involves stablecoin issuers partnering with blockchain protocols or DeFi platforms to prioritize their tokens over others. For example, a stablecoin issuer might enter exclusive agreements with a DeFi protocol to ensure its token is the default for lending or trading, stifling competition. Courts would evaluate these arrangements under the “rule of reason,” weighing pro-competitive benefits (e.g., network efficiency) against anti-competitive harms (e.g., reduced consumer choice). The decentralized nature of blockchain complicates this analysis, as identifying the parties to an agreement—especially in pseudonymous networks—poses enforcement challenges.

Sherman Act Section 2: Monopolization and Market Power

Section 2 targets unilateral conduct that creates or maintains a monopoly through exclusionary practices. In the stablecoin market, Tether’s dominance—holding over 50% of the market share—raises questions about monopolistic behavior.

To establish a Section 2 violation, regulators must define the relevant market, prove the defendant’s monopoly power, and demonstrate exclusionary conduct.

Defining the Market:

The relevant market could be narrowly defined as “dollar-pegged stablecoins” or broadly as “digital payment instruments,” including cryptocurrencies, credit cards, and fiat-based systems. A narrow definition favors finding monopoly power, given Tether’s dominance, while a broader definition dilutes this power by including diverse competitors. Blockchain’s role as the infrastructure for stablecoin transactions further complicates market definition, as control over a blockchain network (e.g., Ethereum’s dominance in DeFi) could confer indirect market power.

Monopoly Power:

Tether’s market share and control over USDT’s reserves suggest significant market power. However, stablecoin markets are dynamic, with new entrants like PayPal’s PYUSD and potential government-issued stablecoins (e.g., Wyoming’s proposed token). Barriers to entry, such as regulatory compliance costs and network effects (where users gravitate to established tokens), could entrench Tether’s position. Blockchain governance also matters: if a stablecoin issuer influences a blockchain Blockchain network’s consensus mechanism (e.g., by controlling validators), it could exclude competitors, reinforcing monopoly power.

Exclusionary Conduct:

Exclusionary practices might include predatory pricing (offering below-cost transaction fees to drive out rivals), refusing to interoperate with competing blockchains, or leveraging reserve assets to manipulate markets. For instance, a stablecoin issuer could flood a DeFi protocol with liquidity to crowd out smaller tokens, then raise fees once competitors exit. Proving intent is critical, and blockchain’s transparency—where transactions are publicly recorded—could aid regulators in tracing such conduct.

Blockchain-Specific Challenges

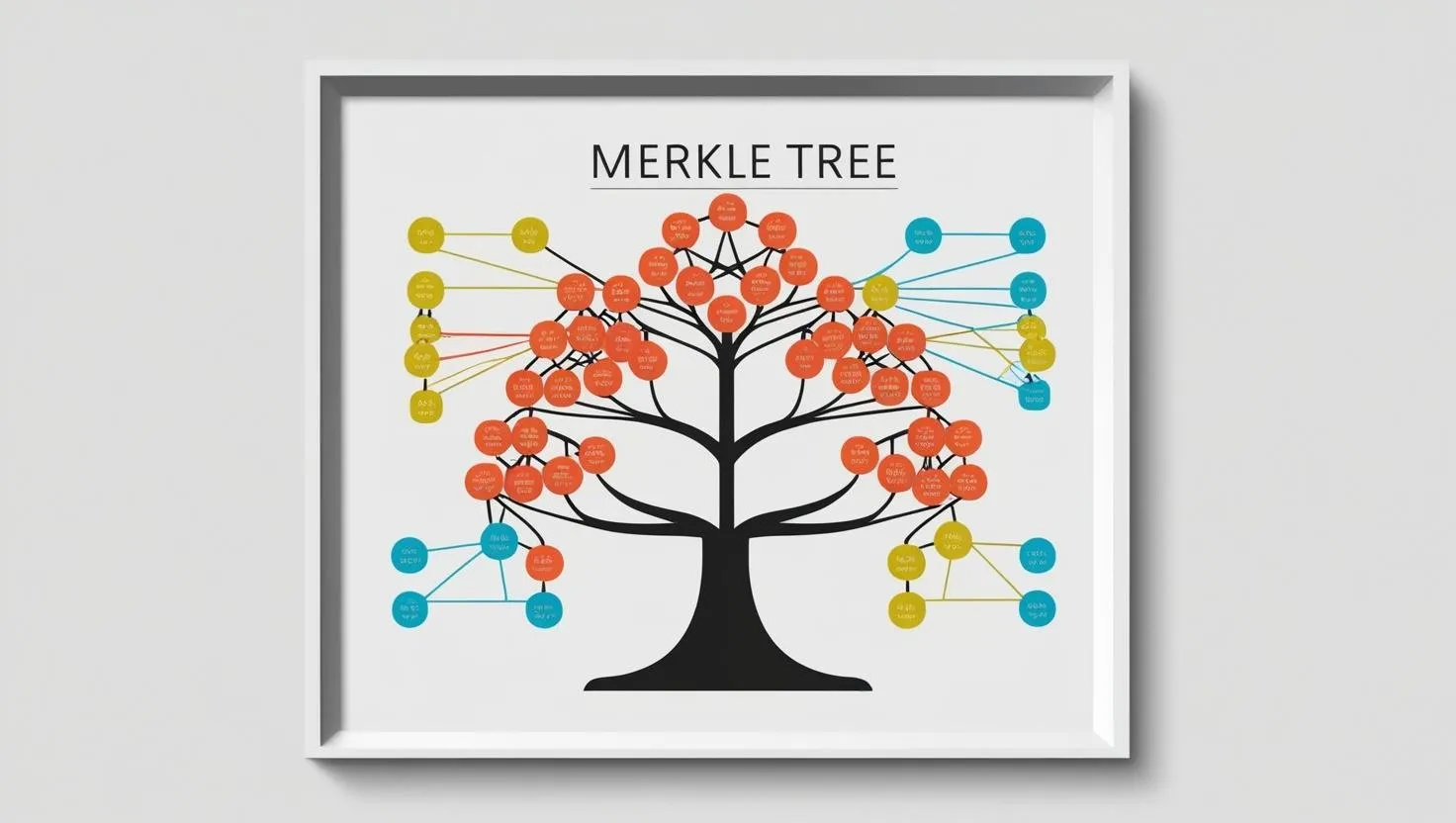

Blockchain’s decentralized structure poses unique challenges for Sherman Act enforcement. First, identifying liable parties is difficult in pseudonymous networks where developers or validators may be anonymous or offshore. Second, the global nature of blockchain complicates jurisdiction, as stablecoin issuers and nodes operate across borders. Third, open-source protocols, like Ethereum, are not owned by a single entity, raising questions about who is responsible for anti-competitive effects.

For example, if a DeFi protocol’s code inherently favors one stablecoin, is the developer, the community, or the issuer liable?

Smart contracts—self-executing blockchain programs—add another layer. If a smart contract automates anti-competitive behavior (e.g., excluding certain tokens), liability may hinge on who deployed it and whether they foresaw the effects. Courts may need to adapt traditional antitrust principles to address these novel issues, potentially treating blockchain networks as “essential facilities” that must provide non-discriminatory access.

Regulatory and Legislative Context

The Sherman Act operates alongside emerging stablecoin regulations, such as the GENIUS Act and STABLE Act, which impose reserve requirements and anti-money laundering rules but do not directly address antitrust. These laws clarify that stablecoins are not securities, reducing SEC oversight and shifting focus to banking regulators like the OCC and Federal Reserve. However, antitrust enforcement remains under the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which have yet to bring major cases against stablecoin issuers or blockchain platforms.

Recent legislative proposals, like the Clarity for Payment Stablecoins Act, exclude stablecoins from securities laws but subject issuers to bank-like oversight. This could indirectly curb anti-competitive behavior by mandating transparency and reserve audits, making collusion or predation easier to detect. Yet, the lack of comprehensive federal stablecoin regulation leaves gaps, with states like New York imposing their own rules (e.g., BitLicense).

Case Studies and Hypotheticals

Consider a hypothetical: Tether partners with a major blockchain to integrate USDT as the exclusive stablecoin for transaction fees, sidelining USDC and DAI. This could violate Section 1 if it stems from an agreement to restrain trade or Section 2 if Tether leverages its dominance to exclude rivals. Proving harm requires showing reduced innovation, higher costs, or consumer lock-in, but blockchain’s transparency could reveal transaction patterns supporting the case.

In a real-world example, the SEC’s 2023 case against Binance (not a Sherman Act case) alleged market manipulation involving stablecoins, hinting at practices that could trigger antitrust scrutiny. Similarly, concerns about Tether’s reserve transparency have sparked debates about whether its dominance distorts DeFi markets, though no antitrust action has been filed to date.

Policy Implications and Future Directions

Applying the Sherman Act to stablecoins and blockchain requires balancing innovation with competition. Overenforcement could stifle blockchain’s potential to disrupt traditional finance, while underenforcement risks monopolies that harm consumers.

Regulators should prioritize:

- Market Definition Clarity: Courts and agencies must define stablecoin markets consistently, considering blockchain’s role as both infrastructure and competitive arena.

- Data-Driven Enforcement: Blockchain’s public ledger offers a trove of data for detecting collusion or predation, but regulators need technical expertise to analyze it.

- Global Coordination: Given blockchain’s borderless nature, U.S. regulators should collaborate with jurisdictions like the EU, which regulates stablecoins under MiCA.

- Tailored Remedies: Remedies like divestitures may not fit blockchain, but mandating interoperability or open access to networks could restore competition.

The DOJ and FTC should also monitor DeFi protocols and stablecoin integrations, as these are hotspots for anti-competitive conduct. As blockchain evolves, Congress may need to amend the Sherman Act or pass new laws to address decentralized systems explicitly.

Conclusion

The Sherman Act’s principles—preventing collusion and monopolization—are highly relevant to stablecoins and blockchain, but their application demands nuance. Stablecoin issuers like Tether face scrutiny for market dominance, while blockchain networks raise novel questions about liability and governance. As the stablecoin market grows and legislation like the GENIUS and STABLE Acts shapes the regulatory landscape, antitrust enforcement will play a critical role in ensuring competition and innovation. By adapting traditional legal frameworks to this digital frontier, regulators can foster a vibrant, competitive ecosystem that benefits consumers and preserves the transformative potential of blockchain technology.